Western

and Mäori Values for Sustainable Development

David

Rei Miller,

Ngäti

Tüwharetoa, Ngäti Kahungunu,

MWH

New Zealand Ltd

Forestry,

fishery and agriculture account for $1 billion of the $1.9 billion Māori

economy annually, but these industries are under threat from environmental

destruction and unsustainable resource use. Māori

leaders of today and tomorrow must negotiate the interface between Te Ao Māori

and Western science to ensure long-term sustainability of the environment,

society, economy and cultural values.

This

paper examines the Māori

and Western scientific worldviews, describing the fundamental differences and

emerging similarities found at the interface. The emerging mindset in Western

sustainability science has notions compatible with and complementary to mātauranga

Māori.

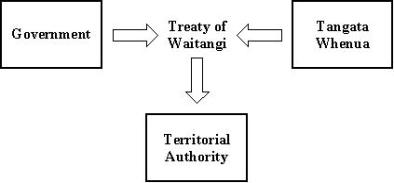

The current legislative framework requires and enables partnerships between

Tangata Whenua and local government in resource management.

Case

studies are given that strive to meet the objectives of both parties. In

general, these have proved successful, but there are areas where improvement is

needed. It is concluded that Māori

are well-placed to become world leaders in sustainability.

As the

20th century drew to a close, we began writing a new chapter in the history of

Aotearoa. In 2004, Mäori have greater control over resource management and

decision making than at any time in our colonial past. Treaty settlements, iwi

ventures and partnerships with government have been used to bring the Mäori

economy into the marketplace of the modern world, the global economy. However,

the global economy and humanity in general are now facing enormous challenges

due to resource depletion and environmental degradation. Forestry, fishery and

agriculture account for $1 billion

of the $1.9 billion Mäori economy annually (NZIER, 2003). These industries are

greatly at risk from threats such as global climate change, seasonal algal

blooms, acidification of the atmosphere and unsustainable resource use.

The Māori

leaders of tomorrow must be aware of their unique relationship with the

environment, and of ways in which the long-term sustainability of the

environment, society, the economy and cultural values can be ensured. It is not

enough to simply achieve short-term goals of economic progress. It is necessary

for Māori

leaders to negotiate the interface between Te Ao Māori and Te Ao Whānui, so that Māori can be citizens of the world while still retaining cultural identity.

The four signposts to guide this negotiation are the exercise of control, the

transmission of worldviews, participation in decision-making and the delivery of

multiple benefits (Durie, 2001).

The

objective of this paper is to examine the worldviews of Māori

and Western science with regard to sustainability (the ability to meet the needs

of the present generation while ensuring that the needs of future generations

may be met). The interface between the two worldviews is examined, with the

hypothesis that there is an area of common ground enabling Western and Māori

principles of sustainability to be used for mutual gain. Government legislation

providing a framework for partnerships between Tangata Whenua and local

government to manage resources is described. Several case studies are examined

which strive to meet the objectives of both parties to ensure the sustainability

of the environment, society, economy and cultural values.

Long

ago, Tane Mahuta ascended the poutama into heaven and brought back three

baskets, containing knowledge of the worlds Tua-Uri, Te Aro-Nui and Tua-Atea.

Tua-Uri

is the world of dark that existed before the natural world we now perceive. This

world lasted for 27 nights, each of which spanned an aeon of time. Tua-Uri

cannot be perceived by direct means. It is where cosmic processes originated

that operate as complex, rhythmic energy patterns upholding, sustaining and

replenishing the life energy of the natural world. Tua-Uri is the place where

all things are gestated, evolved and refined before becoming manifest in Te Aro-Nui,

the natural world of sense perception. Tua-Uri and Te Aro-Nui are part of the

cosmic process, but not ultimate reality.

Tua-Atea

is the third world, which is infinite and eternal, existing beyond space and

time. This is the abode of Io, the creator, and is the transcendent, eternal

world of the spirit. It was before Tua-Uri, and is the ultimate reality which Te

Aro-Nui is tending towards.

Throughout

the genealogy of the cosmic process, mauri, hihiri, mauri-ora and hau-ora occur

at different stages. Mauri occurs early on in the genealogy of the cosmic

process. It is the force that penetrates and binds all things. As the various

elements of the universe diversify, mauri acts to keep them all in unison.

Hihiri is pure energy, manifested as radiation or light. It is a refined form of

mauri and is an aura which radiates from matter, especially living things. Mauri-ora

is the life principle, further refined beyond hihiri. Mauri-ora is the binding

force that makes life possible. Hau-ora is the breath of the spirit, infused

into the cosmic process to give birth to animate beings. The genealogy from hau-ora

through to Ranginui and Papatuanuku is shown in

Figure 1

:

Figure 1:

Early Genealogy of the Universe (Marsden and Henare, 1992)

|

|

|

Hau-Ora |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Shape |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Form |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Space |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Time |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ranginui |

|

Papatuanuku |

||

From the

union of Ranginui and Papatuanuku came the atua, including Tane Mahuta guardian

of the forest, Tangaroa of the ocean, Haumietiketike who presided over wild

foods and Rongomatane whose domain was cultivated crops. The resources under the

protection of each atua emanate from them, and have spiritual and physical

aspects.

Hineahuone,

the first human, was created by Tane breathing life into the earth. Humans are

both descended from and created by the atua, and hold both divine and mortal

principles.

The

worldview of the Māori is expressed most frequently through the use of myths or legends. Māori

myths and legends form the central system on which a holistic view of the

universe is based.

Myths and legends were neither fables

embodying primitive faith in the supernatural, nor marvellous fireside stories

of ancient times. They were deliberate constructs employed by the ancient seers

and sages to encapsulate and condense into easily assimilated forms their view

of the world of ultimate reality and the relationship between the creator, the

universe and man.

(Marsden and Henare, 1992)

Atua

provided a rational and orderly way of living and perceiving the environment.

For Māori the

environment exists on several different levels at once. A mountain can be the

personification of a particular atua, as well as being rock, a resource to be

utilised, and having qualities such as beautiful or cold. This worldview has a

number of connotations for resource gathering and management. The appropriate

karakia must be spoken when gathering resources, for example when felling a tree

to ensure the blessing of Tane Mahuta. Desecration of resources is destruction

in a physical sense, but also an insult to the spiritual powers who created them

(Kawharu, 1998).

The physical world was these atua. Tane was

a tree, also Tane was a person, likewise, water was Tangaroa. They were not

silly, they knew water was wet and all that, but they also knew it as Tangaroa.

(O’Regan, 1984)

Māori

perceptions of reality (in other words, what was regarded as actual, probable,

possible or impossible), were deliberately placed in symbolic mythology for

several reasons. Firstly, this enabled them to easily imprint upon the mind,

allowing finer details to be added in progressive order, until the entire body

of knowledge was learned. At the same time, however, due to the tapu nature of

knowledge it was desirable to use symbols to hide inner meanings and prevent

misuse or abuse of the information within. Through mythology and genealogy

Tangata Whenua are reminded that they are a product of the environment, rather

than being in a superior position to it. The two myths of Rata and Te Ika a Maui

demonstrate Māori

beliefs regarding the use of resources.

After a

series of events, it came about that Rata needed to fashion a waka to recover

the relics of his father from an enemy. He felled a totara tree for the purpose,

and after his labour left it lying in the forest until the next day. On his

return, he found that the log was no longer there. Looking around he recognised

the tree, growing tall exactly as he had found it. There were not even any wood

chips remaining on the ground. He felled the tree again, this time trimming it

as well, and stripping off the bark before returning home. The next day, the

totara was back in place as though it had never been touched, and not a chip nor

scrap of bark was out of place. Rata once again chopped down the totara, and

this time he trimmed it, shaped it and began to scoop out the inside of a waka

from the trunk.

Rata

left the half-formed waka and returned home. But later that night, he crept back

into the forest. As he approached the spot where the tree lay, he could hear

singing, and see light shining through the trees. Creeping nearer, he could see

the hakuturi of Tane, fairy folk, birds and insects working away to restore the

totara. Birds were carrying leaves and twigs in their beaks. Thousands of

insects swarmed over the log, replacing chips and filling up the hollow.

Angrily, he leapt from the trees to confront the hakuturi. They fled, the

singing ceased and the lights went out. Rata was standing in the forest alone.

He then repented and spoke of his sorrow in cutting down the tree, saying that

he would never cut down a tree again. Then he heard a voice, which said “You

may, but you must ask Tane Mahuta, guardian of the forest and birds for

permission. He created all these trees, and you must ask him when you wish to

use them.”

Maui

decided he wanted to go fishing with his brothers so he hid in their waka. When

the brothers detected his presence, they decided to take him back. Maui refused

though, and told his brothers that they would have to find land, as Maui had

used his powers of karakia to push the waka far out to sea. The brothers became

afraid and Maui told them to go to his fishing grounds. Soon the brothers were

pulling in plenty of fish. Suddenly the hook Maui was using, which was a jawbone

he obtained from his grandmother, caught onto the tekoteko of a wharenui

belonging to Tonganui, grandson of Tangaroa. Soon a great fish appeared, which

eventually became known as Te Ika a Maui.

Maui

left his brothers to look after the fish before dividing it up, while he went to

see a tohunga to free them from the tapu of catching such a large fish. He also

knew that Tangaroa was angry so he wanted to make peace with him. When he

returned his brothers had already begun to cut the fish up. It thrashed and

writhed, and then when rigor mortis set in, the cuts became mountains, rivers

and valleys, which is why the lie of the land in Te Ika a Maui is so bad today.

These

myths show that before resources are taken, karakia must be addressed to the

proper atua. This ensures that nature is treated with due care and respect. If

karakia are not performed correctly, the anger of the atua may be aroused, with

dire consequences. Through their associations with the atua, these myths were

sanctified and became a foundation on which kaupapa (first principles) were

established. From these guiding principles, tīkanga

(custom or practices) could be derived and validated (Walker, 1978).

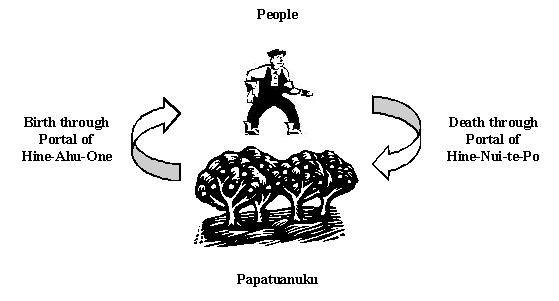

In Te Ao

Māori,

resources belong to the earth, the embodiment of which is Papatuanuku.

Humankind, just like birds, fish and other beings has only user rights with

respect to these resources, not ownership (Marsden and Henare, 1992). The

relationship between Tangata Whenua and the environment is a symbiotic one of

equality and mutual benefit (

Figure 2

).

Papatuanuku

is seen as a living organism, sustained by species that facilitate the processes

of ingestion, digestion and excretion. Pou whenua, the prestige of the land,

relies on marae and human activity for its visible expression (Douglas, 1984),

and the environment also provides sustenance. In return, mankind as the

consciousness of Papatuanuku has a duty to sustain and enhance her life support

systems.

Figure 2:

Tangata Whenua Relationship with Land

Tangata

Whenua are descended from the land, and the word whenua also refers to the

placenta. At birth, this is traditionally buried in the land of the hapu,

strengthening relationships with the land and with whānau.

Land, water, air, flora and fauna are ngā taonga i tuku iho, treasures handed down. Eventually these will be

passed on to ngā whakatīpuranga, one’s descendants. The land gives identity and also

turangawaewae, a place to stand. Without a relationship with the land, Māori

are cut adrift and have no place to stand. Douglas (1984) emphasises that if the

Māori

relationship with land is not recognised, they are obliterated as a people.

Each

hapu will whakapapa back to a particular area of land, a mountain, and a body of

water from which they have sprung. The identification of a hapu with their

surrounding area is so strong that in cases where hapu have moved location for

some reason, they have changed their name accordingly. Within the area of each

particular hapu, resources are managed and accessed collectively, without

individual ownership. Ownership would imply that humans are in a superior

position to the environment, which would be contrary to the Māori

worldview.

Mauri is

a concept of prime importance in Māori

resource management (Morgan, 2004a). Mauri is the binding force between

spiritual and physical; when mauri is extinguished, death results. Mauri is the

life force, passed down in the genealogy through the atua to provide life. It is

also strongly present in water; the mauri of a water body or other ecosystem is

a measure of its life-giving ability (or its spiritual and physical health).

Where mauri is strong, flora and fauna will flourish. Where it is weak, there

will be sickness and decay.

Water is

thus highly valued for its spiritual qualities as well as for drinking,

transport, irrigation and as a source of kai. Bodies of water that hapu include

in whakapapa have mana as ancestors. Their physical and spiritual qualities are

key elements in the mana and identity of iwi, hapu and whānau.

Water is defined in terms of its spiritual or physical state as shown in

Table 1

:

Table 1:

Categories of Water (Douglas, 1984)

|

Waiora |

Purest form of water, with potential to give

and sustain life and to counteract evil. |

|

Waimāori |

Water that has come into unprotected contact

with humans, and so is ordinary and no longer sacred. Has mauri. |

|

Waikino |

Water that has been debased or corrupted. Its

mauri has been altered so that the supernatural forces are non-selective

and can cause harm. |

|

Waipiro |

Slow moving. typical of swamps, providing a

range of resources such as rongoa for medicinal purposes, dyes for

weaving, eels and birds. |

|

Waimate |

Water which has lost its mauri. It is dead,

damaged or polluted, with no regenerative power. It can cause

ill-fortune and can contaminate the mauri of other living or spiritual

things. |

|

Waitai |

The sea, surf or tide. Also used to

distinguish seawater from fresh water. |

|

Waitapu |

When an incident has occurred in association

with water, for example a drowning, an area of that waterway is deemed

tapu and no resources can be gathered or activities take place there

until the tapu is lifted. |

Mixing

water of different types is a serious concern for Māori.

The mauri of a water body can be destroyed by an inappropriate discharge, with

serious consequences for the ecosystem concerned. Hapu reliant on the spiritual

and physical well-being of the water body will also be affected. Mauri is

defined on the basis of catchments (as are tribal boundaries). The diversion or

combining of waters from different sources or catchments is considered

inappropriate.

Kawharu

(1998) examined the set of principles relating to kaitiakitanga, and the

evolution of the term, in detail. This source is heavily drawn on in the current

section.

The word

kaitiakitanga is a recent development, although the underlying principles have

most likely been practiced for hundreds of years. It developed recently as Māori

increasingly sought to demonstrate their political and social status,

particularly in relation to resource management. The word comes from “tiaki”

meaning to care for, guard or protect, and the generic term “kai” which

leads to “kaitiaki” to indicate a guardian, caretaker, conservator or

trustee. Some iwi instead use the term “te hunga tiaki” to avoid juxtaposing

“kai” with “tiaki”, which could cause offence since the word “kai”

is used of food.

Kaitiakitanga

was introduced to encapsulate a wide range of ideas, relationships, rights and

responsibilities. The use of a single word allowed the Crown to translate this

concept into something they could understand. It has variously been translated

to mean “guardianship” or “stewardship”. Stewardship is not a correct

translation, since the implication is that a steward looks after someone

else’s property. Guardianship does fairly well to translate one part of the

concept of kaitiakitanga, that of ensuring the sustainability (long-term

survival) of resources.

Māori

concepts of kaitiakitanga, however, involve a much broader range of principles

and activities than the current Pākehā understanding of the term. Included in kaitiakitanga are concepts

concerning authority and use of resources (rangatiratanga, mana whenua),

spiritual beliefs ascertaining to sacredness, prohibition, energy and life-force

(tapu, rahui, hihiri and mauri) and social protocols associated with respect,

reciprocity and obligation (manaaki, tuku and utu).

The

purpose of kaitiakitanga is to ensure sustainability (of the whānau,

hapu or iwi) in physical, spiritual, economic and political terms. It is the

responsibility of managing resources to ensure survival and political stability

in terms of retaining authority over an area. As well as a practical process,

kaitiakitanga is an exercise of spiritual authority or mana. Through genealogy,

kaitiakitanga becomes a responsibility delegated by the atua. The management of

resources is most often carried out at the hapu level. Kaitiaki are usually hapu

or whānau,

or significant individuals within these groups such as rangatira, tohunga and

kaumatua. Kaitiaki in the spiritual sense could also be taniwha or ancestral

guardians.

The key

feature of kaitiakitanga is reciprocity. The reciprocal agreement between

kaitiaki and resource means that the resource must sustain the kaitiaki

(physically, spiritually and politically), who in return must ensure the

long-term survival of the resource. As well as being conserved, resources were

also there to be used. A hapu has mana whenua or mana moana (rights of resource

use) over a particular area, from which it gains prestige and respect. But the

resources also have mana associated with the ability of the land to produce the

bounties of nature. Reciprocity is a means of keeping balance, and also a way of

insulating the kaitiaki against political, economic or spiritual harm.

Kaitiakitanga,

as well as being a resource management framework and an environmental ethic, is

also associated with the social structure. It is overall a socio-environmental

ethic which delineates relationships humans have with the environment, the atua,

and each other. The most important social dimension of kaitiakitanga is

manaakitanga, providing for guests. This too is a reciprocal arrangement. The

host group provides hospitality predominantly in the forms of shelter,

protection and kai. In return, the visitors are acknowledging the host as

Tangata Whenua, with mana whenua and mana moana in that area. The more the host

gives, the greater their mana. Various districts and marae take pride in the

specialty foods of their area, particularly in regard to kai moana. In customary

times, it was the exercise of the rights and responsibilities of kaitiakitanga

that proved an association with and ties to an area or resource, distinguishing

a group as Tangata Whenua. Kaitiakitanga was a right delegated by the atua, but

these rights had to be asserted. Principally this was done through occupation,

hosting guests, naming features, marae, taonga, burial grounds and oratory.

An

important dimension of kaitiakitanga was tuku (similar to the concept of lease),

through which a hapu with mana whenua or mana moana would grant temporary user

rights to another hapu. This allowed a neighbouring hapu or a related hapu to

become kaitiaki within a certain area, but with an obligation to give something

in return. This was as much a social alliance between hapu as it was a practical

operation, and often occurred in return for the promise of warriors, as a peace

offering, or as compensation. Mana whenua or mana moana was not transferred, and

the group receiving tuku did not usually use the land or resources as if they

had mana over them (for example, their dead were not buried on tuku land). Tuku

would either be short-term (1-2 generations at most) or long-term, in which case

the rights to manage land and resources may eventually be combined (for example

through marriage). In some cases, it was made implicit that title remained with

the original rangatira. These cases were referred to as tuku rangatira. Other

concepts similar to tuku were taiapure, which involved coastal iwi setting aside

areas for inland iwi to fish, and mataitai, which similarly set aside areas for

shellfish gathering.

Kaitiakitanga represents a number of concepts that tie together the

physical, environmental, spiritual, economic and political aspects of Māori

society. It establishes relationships humans have with the environment, the

spiritual world and each other. It also provides a means through which hapu

identify with an area or resource and strengthen their ties to it. In

particular, kaitiakitanga provides a framework in which practices for

responsible management of resources may function.

According

to Kawharu (1998), Māori resource management philosophies and practices were highly structured

and organised. The Māori lunar calendar (maramataka) had a specific name for every day of the

month, each day being important for particular activities (e.g. planting,

harvesting or fowling). Various practices were, and still are used by Māori

to ensure the long-term survival of resources, and therefore hapu and iwi.

The most

notable of these practices was rahui, a ritual prohibition enforced to

temporarily remove a resource from use. Rahui is implemented whenever the mauri

of an area or resource is in jeopardy through over-use or some other significant

event. The most frequent reason for placing an area under rahui is to allow time

for a resource to recover from over-use. But rahui could also be put in place

where a resource was marked out for a particular purpose (e.g. a certain tree

for use as a waka) or to be harvested for a significant event (such as a tangi

or tribal gathering). If there was a death at sea and the body not found, rahui

would be implemented on resources in the area. Rahui was sometimes used as a

form of agricultural rotation, removing individual areas from use on a cyclic

basis.

When

rahui is implemented, a tohunga will perform a karakia asking the relevant

spiritual powers to intervene, render the area tapu (sacred and prohibited),

offer protection and strengthen the mauri. The enhancing of mauri in the

resource is the key outcome of rahui. Once mauri is restored, the life-giving

ability of the resource will once again flourish. While mauri is not created by

humans, a tohunga could imbue particular objects (such as a building or stone)

with mauri by careful observation of karakia. These objects could then serve as

a vessel for the spiritual powers to promote well-being within an object or

area. Mauri stones were used in this way to aid regeneration during rahui.

Agricultural

practices always involved the use of karakia. On some occasions, a stone or

particular tree may have had karakia performed to give it the authority to

contain the mauri of an entire resource. The object could then act as a vessel

for spiritual powers to mediate, offer protection and ensure that the resource

was well-managed. For example, a significant stone in a kumara plantation would

be selected, through which Rongomatane could intervene and assist with

generating a good crop. In some cases, a kaitiaki such as a lizard would also be

appointed to look after the mauri (Kawharu, 1998).

Karakia

were performed at every stage of managing resources, from early preparation to

harvesting. Offerings were made to atua prior to planting, karakia were recited

to encourage fish into fishing grounds and also before snaring kiore. The

growing season was considered tapu, as were fowling seasons, and even those

engaged in preparing or harvesting resources. Karakia were then subsequently

performed to lift tapu as required. Karakia and tapu were used to discipline the

behaviour of those directly or indirectly involved in resource gathering.

Respect for spiritual authority was important if fish, birds or crops were to be

healthy and plentiful (Kawharu, 1998).

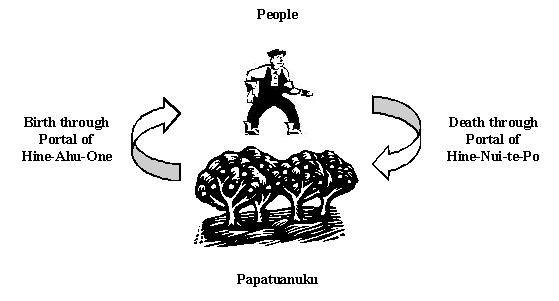

Until

the 16th century the Western world had a holistic view of nature as God’s

plan. The holistic worldview interconnected knowledge of the environment, the

spiritual world and culture, as shown by the circle in

Figure 3

. As rational, scientific

thought began to develop, specialised branches of knowledge emerged.

Figure 3

shows that as this occurred,

each branch became separate from the others, and fragmented from the whole body

of knowledge:

Figure 3: Holistic and Fragmented Worldviews (Morgan, 2004b after Roberts, 2001)

The heliocentric universe of Copernicus was developed solely from a scientific standpoint, without recourse to spiritual or cultural knowledge. In fact, this theory was condemned as heretical. Breaking away from religious and cultural constraints allowed Western science to freely explore the universe, leading to an unprecedented level of detailed knowledge and technological innovations. However, social, cultural, spiritual and environmental concerns soon fell by the wayside. The industrial revolution and technological progress increased our ability to destroy ecosystems, acidify the atmosphere, damage the ozone layer and pollute aquatic or terrestrial environments. In 1798, Malthus predicted that Earth had a finite carrying capacity for the human population, beyond which it could not sustain us. It is largely from considering the impacts that our species has had on the planet that a new movement in Western science began, leading to the development and now implementation of a sustainability ethic.

Until

the turn of the 20th century, Western science viewed the universe as composed of

indestructible atoms of solid matter existing in infinite space and absolute

time.

It

conformed to strict mechanical laws operating in an absolutely predictable

manner. New physicists such as Max Planck (quantum theory), Albert Einstein

(relativity), Werner Heisenberg (uncertainty principle) and others introduced

entirely new concepts.

The

current Western scientific view is that the universe is finite in extent and

relative in time. There is no absolute rest, size or motion. Matter does not

exist of indestructible atoms of solid matter but rather as a complex series of

rhythmical patterns of energy. Under these conditions, the atom needs only a

minimal space and time in which to exist (the uncertainty principle). It is

process, not simply inert matter. The new physicists proposed a construct for

the universe consisting of a real world behind the world of sense perception.

This world cannot be apprehended by direct means, but the concept may be grasped

by speculative means and the use of symbol:

E

= m.c 2

In 1962,

Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring, speaking about the effects of agricultural

pesticides on animal species and human health. This book used Western scientific

principles to show interactions between the economy, the environment and human

well-being. This was a watershed event, and has been referred to as a turning

point in our understanding of these interconnections (Boyle, 2004). The genesis

of sustainability as a concept in Western science was in 1987, when the World

Commission on Environment and Development published the Brundtland Report. This

introduced and defined sustainable development as being:

Development that meets the needs of the

present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to

meet their own needs.

(World Commission on Environment and

Development, 1987)

On a

national level, the New Zealand Society for Sustainability Engineering and

Science (NZSSES) was launched in 2003 to contribute to the development and

implementation of sustainability engineering and science and prepare informed

comment on public policy issues. The NZSSES provides a network through which

engineers, scientists, planners, policy makers and others can make

sustainability a part of all engineering and resource management activities

within New Zealand. The three guiding principles of sustainability as seen by

the NZSSES are:

·

maintaining the

viability of the planet

·

providing for

equity within and between generations

·

solving

problems holistically

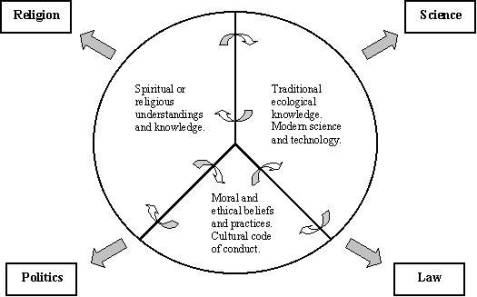

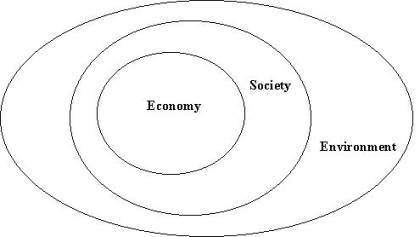

Sustainability

attempts to change the recent narrow-minded focus of Western society on

technological innovation or financial gain. The three pillars of sustainability

are seen as the economic, social and environmental spheres, all of which are

inter-related.

Figure 4

shows the three as distinct,

but with some overlap. Sustainable activities must take place at the

intersection of all three. This model is referred to as weak sustainability,

since it does not accurately represent the real situation. For instance, the

model shows a large part of the economy existing outside the environment, when

in reality it requires the input of natural resources.

Figure 4:

Weak Sustainability

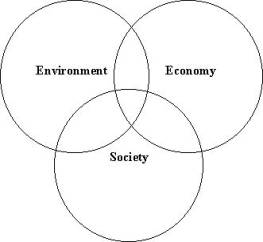

The strong sustainability model (Figure

5

) recognises that the economy only exists within the confines of society,

which in turn only exists within the environment.

Figure 5:

Strong Sustainability

The

differences between the two are highly significant. The strong sustainability

model indicates, quite correctly, that unlimited economic growth is impossible.

The economy only exists to serve members of a society, and it requires the input

of resources from the environment to function. Definitions of the pillars of

sustainability vary somewhat. The Dutch Social-Economic Planning Council uses

people, profit and planet. In the 19th century, Le Play proposed a similar

framework emphasising family, work patterns and environment. Additions to the

three key pillars include cultural, ethical, technical or functional. Where

culture is not allocated a separate category, it must be considered as an

integral part of the social sphere. Technical or functional issues can in some

cases be considered under the economic sphere.

Kettle

(2004) incorporates sub-categories within the three main categories to give the

framework shown in

Table 2

:

Table 2:

Sustainability Categories (Kettle, 2004)

|

PEOPLE |

PROCESSES |

PLACES |

|||

|

Cultural |

Social |

Institutional |

Financial |

Natural

Environment |

Built

Environment |

|

These are the more subjective qualities. |

These processes represent the interactions between people and their

built and natural environment. Institutional refers to legal and regulatory considerations. |

Air/land/water quality and pipes/buildings. The more concrete,

objective qualities. |

|||

Various

sustainability measurement techniques have been developed, the most common of

which is triple bottom line (TBL) reporting. Using TBL reporting, companies that

previously reported only their financial performance are now also measuring and

reporting their impacts on the environment and society. Sometimes, cultural

impacts are assessed separately, in which case this is referred to as quadruple

bottom line (QBL) reporting. TBL reporting provides a pathway for companies to

become more socially and environmentally responsible. Once measurements of

performance are given, targets can be set and improvements made. TBL reporting

also enables shareholders and other interested parties to assess the overall

performance of a company, and take a more holistic approach to investment

decisions. A growing segment of consumers make decisions based on factors other

than quality and price. This is the reason for the increasing popularity of

products such as plant-based washing powder, organic foods and fair trade

coffees. With ethical investors in mind, a Dow Jones Sustainability Index has

been created, ranking companies listed on the stock exchange in terms of

environmental and social as well as economic performance. The Global Reporting

Initiative, associated with the United Nations Environment Programme, was formed

to produce sustainability reporting guidelines that could be applied globally,

to any organisation. The guidelines are currently translated into 10 languages.

A number

of other measurement techniques have been developed on the same principles as

TBL reporting.

Figure 6

shows a technique developed

for a mine site, with scores given for 16 possible environmental or social

impacts specific to the operation. 100

% represents no impact, with greater or lesser scores representing positive or

negative impact. The data behind the construction of this diagram is detailed

enough to be meaningful, but the diagram enables the environmental and social

performance of this mine to be assessed visually, and compared with other sites

or a reference case. The more negative impacts there are, the smaller the shaded

area becomes. This particular site scored well on minimising visual, noise and

dust impacts, but poorly on greenhouse gas emissions and solid waste

minimisation.

Figure 6:

Impacts from Mining (Burkitt and Preston, 2004)

Hellström

et al (2000) proposed a set of criteria which could be used to rank

the overall impacts of a project or process (

Table 3

). These criteria can be used

to compare the relative sustainability of a number of different options at the

planning stage (multi-criteria analysis).

Table 3:

Hellström

Model Criteria (Hellström et al, 2000)

|

Criterion |

Sub-Criterion |

|

Health and Hygiene |

·

availability of clean water ·

risk of infection ·

exposure to toxic compounds ·

working environment |

|

Social and Cultural |

·

easy to understand ·

acceptance |

|

Environmental |

·

groundwater preservation ·

eutrophication ·

contribution to global warming ·

spreading of toxic compounds ·

use of natural resources |

|

Economic |

·

capital cost ·

operation and maintenance cost |

|

Functional and Technical |

·

robustness ·

performance ·

flexibility |

The

above measures of sustainability enable negative impacts to be quantified with a

view to reducing them, but there is increasing concern that this does not

suitably address sustainability. TBL reporting is sometimes used as little more

than a marketing tool to differentiate a company and provide competitive

advantage. It must be remembered that the overall goal is sustainability, not

simply receiving a good report card, as illustrated by the following quote

(Kettle, 2004 after Daly, 1996):

It is well known that TB patients cough less

as they get better. So the number of coughs per day was taken as a quantitative

measure of the patient’s improvement. Small microphones were attached to the

patient’s beds, and their coughs were duly recorded and tabulated. The staff

quickly perceived that they were being evaluated based on the number of times

their patients coughed. Coughing steadily declined as doses of codeine were more

frequently prescribed. Relaxed patients cough less. Unfortunately the patients

got worse, precisely because they were not coughing up and spitting out the

congestion. The cough index was abandoned.

The cough index totally subverted the

activity it was designed to measure because people served the abstract

quantitative index instead of the concrete qualitative goal of health.

(Daly, 1996)

Donnelly

and Boyle (2004) found that sustainability measurement techniques were not a

practical tool for engineers to use on an everyday basis, except for the

assessment of large projects with significant budgets and personnel available.

The techniques were found to be too complicated, too data and time intensive and

too expensive. Also, the measures are most often applied at the site or project

level, when what is really needed for sustainability is coordinated, integrated,

multi-disciplinary planning at the regional level. Threats to the sustainability

of critical systems and processes need to be identified, and actions taken to

address them. Reporting techniques are generally focussed on the past and the

short-term future, whereas sustainability should ideally focus on the medium

term (50-100 years) and the long-term (1000 years). Boyle (2004) advocates

risk-based future thinking as an alternative to sustainability reporting

techniques. In risk analysis there is always some chance of failure, which is

realistic in terms of resources, since there will always be some possibility of

natural disaster. Boyle assumes that society will still exist 1000 years from

now, stating that we must acknowledge this and plan accordingly. Planning

involves realising that:

Using

this technique, sustainability is measured as the probability of activities

being able to continue without damage to the environment or society or economy.

Full sustainability is considered as less than 5 % risk over 1000 years.

Donnelly and Boyle (2004) concluded that technological advances alone are

insufficient to ensure sustainable development. Far reaching social, cultural,

economic, regulatory and institutional changes are also required, collectively

referred to as the eco-restructuring of society.

Well-being is a final goal, only meaningful

if it is sustainable in the long term. Wealth is an intermediate goal, valuable

when it contributes to the final goals, and not when it does not. Growth,

efficiency and consumption are also intermediate goals, not ends in themselves.

Sustainability engineering is necessary but will never be more than part of what

is needed by society, for the journey towards sustainability. A complete

revision of the nation’s economic goals is probably the most important plank

of a sustainability policy. Sustainable development is at base a moral issue.

(Peet, 2004)

Sustainability

concerns were addressed by the leaders of almost 150 nations at the 1992 Earth

Summit in Rio de Janeiro. A global sustainable development action plan known as

Agenda 21 was negotiated and agreed on, and four international treaties were

signed (on climate change, biodiversity, desertification and high-seas fishing).

The United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development was established to

monitor the implementation of these agreements and act as a forum for the

ongoing negotiation of international policies on environment and development.

International

policies now in place include the Montreal Protocol (1987) which phased out the

use of chemicals depleting the ozone layer, and the Kyoto Protocol (1997) which

sets targets for signatory countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and slow

global climate change. These international agreements are crucial to address key

issues affecting the global environment, to empower individual countries to

legislate for sustainable development at a national level, and to ensure as far

as possible that all countries are doing their part in contributing to the

sustainability of the planet.

There is

an increasing interest in developing sustainable technologies and

infrastructure.

A

sustainable wastewater treatment technology has been defined as one that

involves low energy input, cost, maintenance requirement and environmental

impacts (Pratt et al, 2004).

Sustainable nutrient removal technologies to reduce the impacts of on-site

wastewater on groundwater and surface water bodies were investigated by Pratt et

al . For phosphorus removal, wastewater can be passed over rock filters.

Removal of phosphorus has in the past been achieved by chemical precipitation,

involving the addition of chemicals and creates a waste sludge problem. The rock

filter technology investigated was low cost, simple and required little energy

input. In addition, there is potential to use waste slag from a steel mill as a

rock filter media, meaning that this could be diverted from landfill.

The use

of a foam media biofilter for nitrogen removal in on-site wastewater treatment

systems was also studied. This involves the growth of microorganisms on foam

media for the conversion of NH3/NH4+ to NO2-/NO3-

and subsequently inert N2 gas which escapes to the atmosphere. In a

foam media biofilter, these two conversion processes occur in a single chamber,

reducing the size and cost of system required. Conventional alternatives to foam

media biofilters have included aerated treatment plants, which require forced

aeration and therefore high energy input, or zeolite filters which simply store

nitrogen for off-site disposal. Foam media biofilters, on the other hand,

require no forced aeration and result in an inert end product.

Examples

of sustainable development are occurring through assistance programmes in

developing nations. Funded by organisations such as the Asian Development Bank,

these programmes focus not only on environmental sustainability, but also the

use of local resources to benefit the local economy, plus a commitment to

decentralisation and local empowerment (Tolley et al, 2004). The philosophy behind local empowerment is that aid

creates a dependent society, whereas the aim of sustainable development is to

develop society, and encourage people to take ownership of their infrastructure

and resources. This is accomplished by ensuring that development projects:

·

adapt to local

materials and resources

·

adapt to social

and cultural conditions

·

optimise the

integrity of built structures

·

set up the

skills base, management systems and community ownership necessary for

sustainability

Human

resource development lies at the heart of sustainability. This need for

sustainability education is also recognised by other sustainability advocates.

It is recognised that at present there is a gap of critically thinking

practitioners who have a combination of the passion for a sustainable future and

an understanding of the practical realities needed to effect that change (Mamula-Stojnic,

2004). Similarly, it has been reported that employers complain of engineers

graduating with little knowledge of how their work affects and is affected by

social and economic concerns (Kelly, 2004). On the positive side, it can be seen

that there is a definite shift in Western scientific thinking, and a move

towards a more sustainable future. This emerging mindset is expected to gain

support and eventually replace the current dominant mindset (

Figure 7

,

Table 4

).

Figure 7:

Growth of the Emerging Mindset (Peet, 2004)

Table 4:

Dominant and Emerging Mindsets (Peet, 2004)

|

Dominant Mindset |

Emerging Mindset |

|

Growth

is always good. |

We

exist in a world of limits. |

|

Markets

alone can solve all problems. |

Markets

don’t measure everything that is important. |

|

We

are separate from nature. |

We

are an integral part of nature. |

|

Problems

are caused by the behaviours of others. |

Often

the structure of systems causes problems. |

Humans

perceive the world through a cultural filter. The worldview of any person is

biased by their cultural background, and each culture patterns perceptions of

reality into its own interpretations of what are actual, probable, possible or

impossible. There are a number of fundamental differences between the worldviews

of mātauranga Māori and Western science. But at the same time, emerging trends in

sustainability are creating an area of common ground. Morgan (2004b) following

the work of Mere Roberts identified underlying similarities and differences

between the knowledge systems of indigenous knowledge and Western science.

Western science is silo thinking with a

treatment paradigm. Indigenous knowledge is holistic thinking with a healing

paradigm.

(Morgan, 2004b)

The

treatment paradigm of Western science is seen in the effects-based thinking of

concepts such as TBL reporting. The healing paradigm of tīkanga

Māori

is expressed in practices such as rahui. In Te Ao Māori, spiritual and physical realities cannot be considered as separate

entities. The way in which the spiritual and physical co-exist as two parts of

the whole is symbolised in the pikorua pattern shown in

Figure 8

. Kawharu (1998) after

Marsden (1988) states that reality consists of a complex series of energy

patterns transcending spiritual and material worlds.

Figure 8:

Pikorua Pattern

In

contrast, current Western society is seen as being value-free, materialistic,

analytical and mathematical:

Today’s society requires that we put our

hearts in a safe deposit box, and replace our brains with pocket calculators. I

do not accept this attitude. Without spirituality, humankind will cease to

exist.

(Morgan, 2004b after Mander, 1991)

The

separation between the spiritual and physical has great implications when it

comes to relationships with the environment. The Māori

connection to the land is emphasised through genealogy. Conversely, modern

Western society treats land as a commodity. Morgan (2004b) uses the case of the

Auckland region to emphasise the differences in thinking. On the one hand, the

land is Te Ika a Maui and also the personification of Papatuanuku. As a living

being it must be treated with respect. On the other hand, the Auckland region is

seen as a collection of land designations, to be exploited, although with some

legislative constraints. Morgan (2004b) also cites different cultural attitudes

to pregnancy and afterbirth as indicative of overall attitudes towards land. In

Māori

culture, the whenua is buried in the land at a significant site to strengthen

the connection with Papatuanuku. Western science teaches us that the placenta is

hazardous waste, to be disposed of accordingly. The relationship that Tangata

Whenua have with the land is emphasised by Tīpene O’Regan:

I was challenged recently by a very earnest

Christian who declared: “Surely nature is for all of us - we share it.”

I replied, “Yes, I am quite happy to share

it. But what I want you to recognise is that if we are sharing it, well and

good, but it is we that are the descendants from it.”

(O’Regan, 1984)

Table 5

shows some of the

fundamental differences that exist between the Māori

and Western scientific worldviews. It should be noted that many of the Western

scientific views are those of the dominant mindset, which are gradually being

eroded. This comparison can then be considered a kind of worst-case scenario,

emphasising as many differences as possible.

Table 5:

Key Fundamental Differences

|

Concept |

Mātauranga

Māori |

Western Science |

|

General |

·

holistic thinking with a healing paradigm |

·

silo thinking with a treatment paradigm |

|

Spirituality |

·

intertwined with and inseparable from the

physical world |

·

separate from rational, scientific thought |

|

Values

in Knowledge System |

·

value-laden |

·

value-free |

|

Theory

vs Intuition |

·

use of intuitive learning |

·

strong reliance on theory |

|

Explanations

of Cause and Effect |

·

include all natural and supernatural

phenomena, metaphor and narrative |

·

objective, analytical, ideally mathematical,

value-free |

|

Transmission

of Knowledge |

·

traditionally oral |

·

almost exclusively written |

|

Access

to Knowledge |

·

tapu knowledge restricted to those considered

worthy |

·

free access to knowledge, except where

confidential or classified |

|

Relationship

with Land and Resources |

·

symbiotic and reciprocal, descended from land |

·

ownership, humans separate from land |

|

Whenua/Placenta |

·

buried as connection to land and whānau |

·

considered hazardous waste |

|

Attitude

to Water |

·

special significance as containing mauri |

·

resource to be exploited or used for

recreation |

|

Disposal

of Wastewater into Water |

·

destroys mauri of water and is offensive |

·

acceptable, depending on level of treatment |

|

Diverting

or Combining Waters across Catchments |

·

major concern as inappropriate or offensive |

·

not a concern, depending on availability of

water |

Differences

in allowing access to knowledge within each system may seem minor at first, but

they have far-reaching implications. The higher levels of traditional Māori

knowledge are tapu, and imparted only to someone who has proved that they are

worthy of holding such knowledge without abusing it. The inherent dangers are

explained in this quote from Marsden and Henare (1992):

One of the elders who had of course heard of

the atom bomb asked me to explain the difference between an atom bomb and

explosive bomb. I took the word hihiri, which in Māoridom

means pure energy. Here I recalled Einstein’s concept of the real world behind

the natural world as being comprised of rhythmical patterns of pure energy and

said to him that this was essentially the same concept.

He then exclaimed: “Do you mean to tell me

that the Pākehā

scientists have managed to rend the fabric of the universe?”

I said, “Yes.”

“I suppose they shared their knowledge

with the politicians?”

“Yes.”

“But do they know how to sew it back

together again?”

“No!”

“That’s the trouble with sharing such

tapu knowledge. Politicians will always abuse it.”

(Marsden and

Henare, 1992)

The

current Western scientific understanding of the universe is that matter does not

exist of indestructible atoms of solid matter, but as a complex series of

rhythmical patterns of energy. This is analogous to the Māori

concept of Tua-Uri, the world of dark which existed before the natural world,

and continues to contain the cosmic processes that operate as complex, rhythmic

energy patterns which sustain our world.

The

three sustainability principles of the NZSSES (viability of the planet,

inter-generational equity and holistic problem solving) are also at the heart of

the Māori view of resource management. Kaitiakitanga has manifold aspects

relating to the social, cultural, economic, political and environmental spheres.

Sustainability science also strive to achieve a holistic view by considering

these different aspects.

The key

similarities identified between Western and Māori

views of sustainability and resource management are shown in

Table 6

. Many of these have only

come about recently, through the development of sustainability principles and

the growth of the emerging mindset.

Table 6:

Key Similarities

|

Concept |

Mātauranga

Māori |

Western Science |

|

Underlying

Structure of the Universe |

·

world of Tua-Uri composed of complex,

rhythmical patterns sustaining the natural world |

·

all matter is composed of complex, rhythmical

patterns of energy |

|

Spatial

Extent of the Universe |

·

finite |

·

finite |

|

Knowledge

System |

·

general similarities in accumulating,

systemising and storing information |

·

general similarities in accumulating,

systemising and storing information |

|

Holistic

View |

·

kaitiakitanga encompassing society, culture,

economy, environment and political |

·

sustainability of environment, society and

economy |

|

Resource

Managers |

·

kaitiaki |

·

local government |

|

Providing

for Future Generations |

·

ngā whakatīpuranga |

·

inter-generational equity |

|

Limitations

on Resource Use |

·

rahui |

·

quotas, size restrictions, resource consents |

|

Temporary

Resource Use Rights |

·

tuku |

·

lease |

|

Conservation |

·

species and landscape are taonga |

·

amenity values |

|

Measurement

of Long-Term

Viability |

·

mauri |

·

sustainability |

|

Potable

Water for Flushing Toilets |

·

destroys mauri of water and is offensive |

·

wasteful, expensive and therefore

unsustainable |

|

Stormwater |

·

permeable surfaces prevent contamination of

freshwater |

·

permeable surfaces reduce flooding |

|

Significant

Areas |

·

tapu areas |

·

heritage areas |

Despite

some fundamental differences, there is an increasing area of common ground

between Western sustainability science and mātauranga

Māori.

The

management of resources in Aotearoa/New Zealand is theoretically conducted by

Tangata Whenua and central government, in a partnership initiated through the

Treaty of Waitangi (1840). Central government passes legislation affecting

resource management and decision making at a local level, which is regulated by

a system of regional, district and city councils (Figure

9):

Figure 9:

Resource Management Hierarchy (Morgan, 2004a)

The

English version of the Treaty of Waitangi (1840) guaranteed to iwi:

…the full exclusive and undisturbed

possession of their Lands and Estates, Forests, Fisheries and other properties

which they may collectively or individually possess so long as it is their wish

and desire to retain the same in their possession.

(Article the Second, Treaty of Waitangi,

1840)

The Māori

version of the Treaty on the surface appears to have words to much the same

effect, guaranteeing to iwi:

…tino

rangatiratanga o ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa.

(Ko te Tuarua, Tiriti O Waitangi, 1840)

But

differences between the concepts of tino rangatiratanga and title extinguishment

have caused a great deal of conflict over the years. Holding tino rangatiratanga

over land implies that kaitiakitanga can, and must be practiced by Tangata

Whenua. When Māori

gave up possession of their land to Europeans it was usually assumed they would

retain tino rangatiratanga and mana whenua, as would have occurred under tuku,

and as seemed to be guaranteed by Te Tiriti. The European purchaser, on the

other hand, would naturally have been under the impression that all ownership

rights were transferred, and previous title extinguished.

Without

going into detail, there have been numerous instances where Māori

were deprived of the ability to exercise kaitiakitanga (through tino

rangatiratanga), in direct contravention of Te Tiriti. The Waitangi Tribunal

found in each of the Whanganui River report (1999), the Mohaka River report

(1992) and the Te Ika Whenua report (1998) that the rivers under claim were and

still are the taonga of iwi, and that the Crown had breached Treaty principles.

The Tribunal recommended that the Crown:

·

consult fully

with Māori in the exercising of kawanatanga (governorship)

·

redress Treaty

breaches

·

act towards its

Treaty partner in good faith, fairly and reasonably

Recent

government legislation has sought to restore the exercise of kaitiakitanga, and

has made consultation with Tangata Whenua compulsory where appropriate. This has

provided a framework for resource management to be conducted in true partnership

between iwi and government. Legislation such as the Resource Management Act

(1991) and the Local Government Act (2002) also incorporates the need for

sustainable development, with the use of both Western scientific and Māori

concepts. Local authorities are required to act within the confines of such

legislation, and so the system we currently have is now closer to that shown in

Figure 9 than it has ever been.

The

Resource Management Act (1991) incorporated a range of Māori

concepts, including some newly introduced into New Zealand legislation. Concepts

referred to include kaitiakitanga, mana whenua, Tangata Whenua, tīkanga

Māori

and wāhi

tapu. The Resource Management Act also introduced new Western scientific

concepts such as sustainable development, renewable energy and amenity values

(which are the intrinsic values that ecosystems have of their own right). The

concept of mauri was initially contained in the Resource Management Bill, but

was replaced by amenity values on the basis that the legal system could not cope

with the concept of mauri at the time (Morgan, 2004a). Features of the Resource

Management Act relating to Māori and to sustainability are summarised in

Table 7

:

Table 7:

Features of Resource Management Act (1991)

|

Concept |

Features |

Sections |

|

Purpose

of Act |

·

to promote sustainable development |

5

(1) |

|

Definition

of Environment |

·

includes environment, society, culture,

economy and amenity values |

2

(1) |

|

Definition

of Sustainable Development |

·

meeting present needs while ensuring future

needs can be met ·

safeguarding the life-giving capacity of air,

water, soil and ecosystems ·

avoiding, remedying or mitigating any adverse

effects on the environment |

5

(2) |

|

Treaty

of Waitangi |

·

resource managers must take into account the

principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (1840) |

8 |

|

National

Importance of Māori Culture |

·

relationship of Maori and their culture and

traditions with their ancestral lands, water, sites, wāhi

tapu, and other taonga ·

protection of recognised

customary activities |

6

(e) 6

(g) |

|

Resource

Managers Must Have Regard to |

·

kaitiakitanga ·

stewardship ·

efficient use of resources and energy ·

environment, ecosystems and amenity values ·

finite characteristics of resources ·

renewable energy |

7

(a) - 7 (j) |

|

Regional

and District Plans |

·

local authorities must consider resource

management planning documents produced by iwi authorities |

66

(2A) 74

(2A) |

|

Water

Rights |

·

no person may take, use, dam or divert water

in a manner that contravenes a regional plan unless allowed by a

resource consent |

14

(1) 14

(2) |

|

Discharges |

·

no person may discharge any contaminant to

land or water, or from commercial premises to air, unless allowed by

regional plan or resource consent |

15

(1) 15

(2) |

|

Hearings |

·

must be public where possible ·

must avoid unnecessary formality ·

recognise tīkanga Māori

where appropriate ·

receive evidence in Te Reo Māori ·

may exclude public when necessary to avoid

serious offence to tīkanga Māori or avoid disclosing

location of wāhi tapu |

38 42 |

A

resource consent is required under Sections 14 and 15 whenever a water use

activity or contaminant discharge contravenes or is not allowed by a regional

plan. A resource consent may be either notified or non-notified, depending on

the nature of the activity. If a consent is notified, then consultation with

affected parties is required. This may include neighbours or interest groups

such as Forest & Bird, but must always include Tangata Whenua. Consultation

is basically a process by which the person applying for the resource consent

seeks approval for the proposed activity from all affected parties, with the

Environment Court as the final authority in the case of any objections that

cannot be resolved.

City,

district and regional councils are delegated responsibility for local government

through the Local Government Act (2002) and its various amendments. An analysis

of the Local Government Act, and the requirements that it puts on local

authorities, shows that sustainable development and partnerships with Tangata

Whenua are both fundamental concerns (

Table 8

):

Table 8:

Features of Local Government Act (2002)

|

Concept |

Features |

Sections |

|

Purpose

of the Act |

·

provides for democratic local government

recognising the diversity of communities ·

provides for local authorities to promote

sustainable development |

3

(a) 3

(d) |

|

Purpose

of Local Government |

·

to enable democratic local decision-making and

action by, and on behalf of communities ·

to promote the social, economic, environmental

and cultural well-being of communities, in the present and for the

future |

10

(a) 10

(b) |

|

Partnership

with Māori |

·

provide opportunities for Māori

to contribute to decision-making processes ·

take into account the relationship of Māori

and their culture and traditions with their ancestral land, water,

sites, wāhi

tapu, valued flora and fauna, and other taonga. |

14

(1d) 77

(c) 81

(1) 82 |

|

Sustainable

Development Approach |

·

consider social, economic and cultural

well-being of people and communities ·

maintain and enhance quality of environment ·

consider the reasonably foreseeable needs of

future generations |

14

(1h) 77

(1b) |

|

Long-Term

Council Community Plan |

·

identify and report against community outcomes ·

provide integrated decision-making and

co-ordination of resources ·

provide a long-term focus for the decisions

and activities of the local authority ·

provide public participation in

decision-making processes |

93

(6) |

Other

government initiatives targeting sustainability and environmental protection

include:

·

Hazardous

Substances and New Organisms Act (1996)

·

New Zealand

Waste Strategy (2002)

·

Sustainable

Development Programme of Action (2003)

·

Govt3

initiative to improve sustainability in government

·

ratification of

the Kyoto Protocol (1997) and introduction of a carbon tax

Current

New Zealand legislation provides a framework in which resource management and

local government must:

·

work in

partnership with Tangata Whenua

·

strive to

achieve sustainable development

·

consider a

long-term view of the environment, society, culture and the economy

·

be democratic,

with opportunities for public participation in decision-making

While the framework for mutually beneficial sustainable management of

resources now exists, Māori

have often found in the past that reality falls short of these promises.

Western

society is capitalist, consumer based and driven by market considerations.

Decision-making is most often done through cost-benefit analysis. In most cases

even environmental impacts are quantified in this manner, with a cost allocated

to impacts based on the requirement to avoid, remedy or mitigate effects. In

rational Western thinking there is also a disconnection of the physical and

spiritual, the secular and the sacred (Marsden and Henare, 1992). Ngāti

Whatua for example have expressed concern that government legislation does not

provide for spiritual as well as physical dimensions.

The

treatment of Māori

throughout consultation processes has often left much to be desired. Taylor

(1984) relates a series of embarrassing and humiliating early experiences within

the legal system. The consultative process frequently takes place as an add-on,

after the actual decision-making process, and can be condescending to Māori.

Māori

are expected only to conserve and protect resources, rather than use them for

economic gain, and access to productive land has sometimes proved difficult (O’Regan,

1984). According to Morgan (2004a), power is also an issue, as local authorities

are reluctant to share this with Tangata Whenua.

Tangata

Whenua are often seen as nothing more than another interest group, similar for

example to the Forest & Bird Society. The Māori

relationship to and identification with land is not considered. There can also

be fear, mistrust or suspicion of Māori

values and culture since these are not well understood.

Practices

that are highly offensive to Māori

are continuing today, such as the discharging of effluent into water, the mixing

of different types of water, and the diverting or combining of water from

different catchments. The disposal of wastewater to Lake Rotorua has turned the

food bowl of the Tangata Whenua into a toilet bowl (Morgan, 2004a).

Despite

the advancements made in sustainable development, and in fostering partnerships

between iwi and government, Māori

still have serious concerns with:

·

fundamental

aspects of a capitalist, non-spiritual Western society

·

consultation

sometimes condescending

·

expectation to

only consider environmental or cultural values, not economic well-being

·

lack of regard

for Māori cultural values

·

the

continuation of highly offensive practices

These

issues are major stumbling blocks in the way of a mutually beneficial

partnership between iwi and government for sustainable development. For the

goodwill of Tangata Whenua to be given, there is a reciprocal expectation of

trust, of power sharing and a significant role in decision making (Morgan,

2004a).

The loss

and erosion of indigenous knowledge through lack of use or relevance, and the

isolation from its origins in the physical environment is a huge threat to the

cultural identity of hapu. Finally the Tangata Whenua, the people of this land

have nowhere else to go. Nowhere else in the world is it more appropriate to

assert Te Arawa cultural values and beliefs in relation to the environment, than

within the Te Arawa rohe.

(Morgan,

2004a)

Figure

9 showed how Māori

and central government are partners in resource management in New Zealand, as

determined by the Treaty of Waitangi. Considerable difficulties have arisen when

the approaches favoured by Western science and government are inappropriate or

offensive to Māori.

On the other hand, local government and decision makers need to use

decision-making tools that are rational, can be understood, and to demonstrate

that they have followed correct procedures having some scientific basis. There

is thus a need for a decision-making tool that can be used at the Western-Māori

interface, which is where most local government projects are developed. The

mauri model developed by Kepa Morgan of Mahi Maioro Professionals is a set of

assessment criteria similar to the Hellström

model. It uses terms from Western science and mātauranga

Māori

that may be considered analogous. Corresponding to the four aspects of

sustainability (environment, culture, society and economy) are four levels or

spheres: the environment, hapu, community and whānau

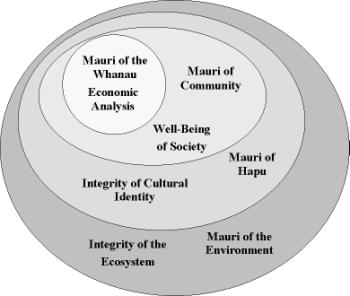

(

Figure 10

):

Figure

10:

Mauri Model (Morgan, 2004a)

The

sizes of each circle reflect the fact that aspects are weighted to give a

greater emphasis to wide-reaching concerns. Note that community refers to the

needs of the community at large (Māori

and non-Māori)

and includes future needs such as land availability, job creation and

recreational opportunities. Generally the weightings used would be 40 %

environment, 30 % hapu, 20 % community and 10 % whānau.

At each level, the effect of a development, project or process on mauri is given

a rating as indicated in

Table 9

:

Table

9:

Rating of Effects on Mauri (Morgan, 2004a)

|

Effect

on Mauri |

Rating |

|

Enhancing |

+2 |

|

Maintaining |

+1 |

|

Neutral |

0 |

|

Diminishing |

-1 |

|

Destroying |

-2 |

Scores

at each level are then multiplied by the appropriate weighting to give a final

result. It should be noted that there are a wide range of factors that determine

the effects on mauri. The assessment of effects should be carried out by Tangata

Whenua or addressed in consultation.

At

first glance, this may seem like another sustainability measurement technique

that does not properly address sustainability. However there are some

significant differences:

·

connections

between levels emphasised

·

mauri as the

life-force is indicative of long-term sustainability

·

mauri includes

spiritual and physical aspects

·

analogous

Western scientific definitions allow easy interpretation

While

the mauri model is intended to be introduced to address some needs specific to Māori,

mauri as the life-giving ability of an ecosystem could also be a valuable

concept in Western sustainability science. Although mauri is a qualitative

measure, it is analogous to indicators such as faecal coliform levels or species

biodiversity used in Western science. Morgan (2004a) gives the example of Lake

Rotorua. The diminished mauri of the lake resulting from wastewater discharges

led to diminished mauri of the community, which manifested itself in cases of

Blue Baby Syndrome. From a scientific standpoint, contamination of drinking

water with nitrates led to infantile methaemoglobinemia, but however it was

described, the overall effect was still the same. Morgan asserts that had the

mauri model been applied, wastewater discharges to Lake Rotorua would not have

been acceptable, and the human health effects could have been avoided.

· contain and immobilise or destroy pathogens

· reduce volume of waste (up to 70 %) and improve handling of final product

·

provide option for on-site disposal where

feasible

Composting

is a process with several strict requirements. There are a number of concerns

expressed regarding the use of DCTs that have proven to be barriers to

widespread use. However, many of these are perception issues only, and represent

resistance from a society that would prefer to flush and forget wastes rather

than take responsibility for treatment. Table

10

shows the requirements of DCTs, concerns that can result from

requirements not being met and also existing solutions to the problems. It can

be seen by examining the table that, depending on factors such as land

availability or local environment, any actual problems associated with

composting toilets can be overcome.

Table

10:

Dry Composting Toilet Requirements and Concerns

|

Requirement |

Potential

Concern |

Solution |

Comments |

|

Airflow |

·

anaerobic conditions ·

no composting ·

odours |

š

natural convection |

·

warm air from compost rises ·